The Nine Kings of the Chakri Dynasty: Rama II – The Poet King

Posted: May 7, 2011 Filed under: History, The Chakri Dynasty | Tags: Ayutthaya, Bangkok, Buddha Loetla Nabhalai, Chakri dynasty, Krung Thep, Rattanakosin Island, Siam, Thailand, the city of angels Leave a commentThe second king of the Chakri dynasty was born in 1767, the same year that Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese. His father was Thong Duang, the man who would later become Rama I. At that time, Thong Duang had been appointed Luang Yokrabat[1] in the provincial town of Ratchaburi, where he met and married Nak (later Queen Amarinda). She gave birth to Chim on February 24, 1767, in Amphawa, Samut Songkhram. Chim was just 16 years old when his father became king and was raised to the title of Prince Itsarasunthon. In 1807 he was appointed uparat (deputy-king) and served as such until his father’s death in 1809, when senior court officials chose him as successor to the throne. However, Prince Thammathibet – the son of Taksin and Rama I’s daughter – plotted to take power for himself with the help of numerous supporters. His plot was discovered before it was implemented and all conspirators were executed, including the prince’s male offspring. After his execution, Prince Thammathibet’s wealth, palace, servants and rice were passed on to the son of the new king-elect. The day after the executions, the anointing ceremony took place and Prince Itsarasunthon officially became king. No royal naming system was established at the time of his accession to the throne. He was later named Buddha Loetla Nabhalai and is commonly called Rama II.

Reformation

During his reign, Rama II introduced numerous reforms. One of the first things he did was to order a complete census of manpower. At the time, Thai society was broken up into four main classes: chao (royalty), khunnang (nobility), phrai (commoners) and that (slaves). Ordinary phrai were expected to perform four months corvée[2], but many of them were able to avoid their duty by circumventing the registration process. In an attempt to remedy this, Rama II issued a decree that aimed to settle all disputes regarding registered status. Runaway phrai were given the opportunity to return to their patrons and were promised that they would not be punished if they did so of their own free will. If they chose to remain in hiding, they would be forcefully arrested and imprisoned. Furthermore, tattooing the wrists of phrai who had not yet been tattooed or had changed status was to be carried out to clearly show who their master (nai) was. The practice of tattooing the wrists of commoners was introduced by King Taksin.

In 1811, Rama II appointed eight committees to the task of surveying all arable land in the central plains area. He ordered that all land must be cultivated and anyone found to own large stretches of uncultivated land would be required to hand it over to the state. All landowners were obliged to pay a land tax, which was usually paid in rice – a tax known as khawka. As well as practical reforms, the king ordered that customary ceremonies were to be carried out before measuring land, such as making offerings to the spirits of the field. People were prohibited from working upon the fields on ceremonial days and anyone caught doing so would have his land confiscated and given to others.

Rama II was a devout Buddhist and he did much to educate the Siamese people on the teachings of the Buddha. He translated the Buddhist texts from Pāli into Thai so that people would understand the prayers and in 1817 he revived the Visakabucha festival, which commemorates the day that the Buddha attained enlightenment and passed into nirvana. When a virulent strain of cholera broke out in 1820, the king relieved all people of their duties so that they could take part in chanting sacred mantras and making merit. All animals were released and allowed to roam freely while prisoners were freed. No living being was to be killed during the ceremony. Not long after, the epidemic abated. The king’s course of action shows his strong belief in the Buddhist concept of karma and it seems he attempted to fight the disease through merit making.

Golden Age of Rattanakosin Literature

It was well known that Rama II was a lover of the arts and in particular the literary arts. He was an accomplished poet and anyone with the ability to write a refined piece of poetry would gain the favour of the king; this led to him being dubbed the “poet king”. It was because of this special circumstance that the poet Sunthon Phu was able to elevate himself from phrai status to khun and later phra[3]. Sunthon – also known as the drunken writer – authored numerous works, many of which are still read and studied today. Rama II rewrote much of the great literature from the reign of Rama I in a modern style. He is attributed with writing a popular version of the Thai folk tale Ramakien and wrote a number of other dance dramas such as Sang Thong. The king was a musician of renown, playing and composing for the fiddle and introducing new techniques for playing certain instruments. He was also a sculptor and is accredited with sculpting the face of the Niramitr Buddha in Wat Arun. Because of his remarkable artistic achievements, Rama II’s birthday is now officially celebrated as National Artists’ Day (Wan Sinlapin Haeng Chat) and is held in honour of those artists who have contributed to the artistic and cultural heritage of the kingdom.

The White Elephant King

The discovery of white elephants in Thailand has always been taken as an auspicious omen and they hold a revered place in Thai society due to their symbolic relationship to monarchy, religion and national identity. Rama II had several white elephants and because of this he was nicknamed “The White Elephant King”. Towards the end of his reign, the death of two white elephants was a cause for great concern and was seen as a sign of impending misfortune. Not long after, on July 21, 1824, Buddha Loetla Nabhalai became ill and died. His reign lasted almost 15 years.

During Rama II’s reign, Siam was mostly a peaceful country and much of his time was dedicated to promoting the arts and religion. He took a somewhat backseat role in the ruling of Siam and preferred to withdraw from administrative duties, leaving much of the work to the nobles. He was the father of 73 children to 40 mothers, outdoing his father in number of offspring but falling short in number of years; he was 16 years younger that Rama I when he died.

[1] “Luang Yokrabat” is a title given to nobility that serve as legal officers, appointed by the king and attached to a provincial centre.

[2] Unpaid labour required of people of low social class.

[3] Khun and Phra are both forms of conferred nobility, with Phra being higher than Khun.

The Nine Kings of the Chakri Dynasty: Rama I – The Founding Father

The Nine Kings of the Chakri Dynasty: Rama I – The Founding Father

Posted: April 20, 2011 Filed under: History, The Chakri Dynasty | Tags: Ayutthaya, Bangkok, Krung Thep, Rattanakosin Island, Siam, the city of angels, The Grand Palace, Thonburi 3 CommentsBetween Two Kingdoms

After the city of Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese in 1767, Siam went through an itinerant period in which the population was displaced and wealth and resources were lost. The Burmese, confident that they had subdued the Siamese forces, withdrew their main armies back to Burma, and left only a few thousand soldiers under the command of a Mon general. This was a fatal error and their occupation of Siam was to be short-lived. Six months after the Burmese had sacked Ayutthaya, a senior officer from the Ayutthayan army, led 5,000 men and more than a hundred boats to the stronghold at Thonburi. He captured and executed the general in charge then proceeded to make Thonburi his headquarters. Before long, he stood out as a strong leader and sometime in 1768 he was chosen as king by popular consent; his name was Taksin. He ruled Siam in an unorthodox fashion and gained the reputation of being impulsive and short-tempered.

During the reign of King Taksin, two brothers rose to prominence as generals in his army. These two brothers were Bunma and Thong Duang. Bunma had been a close ally of Taksin’s during his military campaigns and it was he who convinced his brother to join Taksin’s army. They both became respected generals and in 1778, Thong Duang led an army to the northeast and invaded Laos. He returned to Thonburi triumphant and brought with him the Emerald Buddha statue. This acquisition undoubtedly increased Thong Duang’s prestige and would have been taken as an auspicious sign for the kingdom. He was later promoted to the rank of Chaophraya Chakri, which would be the equivalent of a modern day Field Marshal.

Taksin became more eccentric towards the end of his reign and when he came into conflict with numerous Buddhist monks, his popularity diminished. This, among other things, planted the seeds of his demise. He was later forced to abdicate and took refuge as a Buddhist monk in Wat Chaeng. A succession struggle ensued in which Thong Duang emerged as the strongest contender for the throne. Once he had asserted his power in the capital, he recalled Taksin from Wat Chaeng and put him on trial to face charges of misconduct. Found guilty, he was beheaded on April 7, 1782.

A New Beginning

Not long after taking command, the new king, who later became Rama I or Phra Buddha Yodfa, distanced himself from the reign of Taksin by reversing a number of his decisions and stressing the dignity of the highest office. Fifteen days after been accepted as Siam’s new ruler, Rama I moved the capital from Thonburi to the east bank of the Chao Phraya River. He established the first city pillar and named the new capital Krung Thep. Only foreigners continued to use the old village name, Bangkok.

Construction of the king’s palace proceeded at a feverish pace and it was decided to model the new city on the old capital – Ayutthaya. It seems the king wanted to regain some of the grandeur of Ayutthaya and perhaps rekindle the flames of a golden age in Siamese history. Whatever the reasons, it is known that Rama I ordered ship-loads of bricks to be brought from Ayutthaya and Thonburi to use as basic building materials for the palaces, fortifications and temples. Whether this decision was made due to economic constraints or for ritual value is impossible to say.

On June 6, 1782, Rama I formally ascended the throne in a traditional ceremony in which monks chanted over a container of water for three days before using it to transform the general into a king. The king was carried by palanquin from Thonburi to Bangkok at an auspicious hour. He was then anointed in his palace and presented with a suitable array of royal names. This marked the beginning of the Chakri dynasty, which the present day monarch, Bhumibol Adulyadej, is descended from.

A Stable Siam

Two years after the king’s ascension to the throne, Bangkok was starting to look like a capital city. An audience hall, library and temple had been constructed within the palace compound and an official opening ceremony was held in which the king was anointed a second time. He developed a daily routine which included giving alms to Buddhist monks, discussing court finances and matters of general importance, and listening to sermons in the audience hall. During his daily meetings, the king would regularly request the Department of Registration to disseminate the royal edict. One of these edicts enforced a law prohibiting civil servants from gambling. In the opening preamble of the edict the state of affairs in Siam is revealed: “Nowadays there are but few amongst the populace who are truthful and who make a living in a law-abiding manner.” Gambling was big business at the time and many people made their fortunes from it. Indeed, Rama I later had to revise the law when it became apparent that State revenue was suffering. He allowed gamblers to continue borrowing money but the license-holders were instructed to lend money based on the means of individuals to avoid excessive debt burden.

Another important reform under Rama I was the revision of the Siamese version of the Buddhist Tripitaka. When the king had been informed that many of the old texts contained mistakes, he organised a council of learned men to edit the extant versions and compile a definitive set. The revisions of the text were finished within five months and a festival was organized to commemorate the new Tripitaka. During the festivities, the roof of the library caught fire as a result of the firework display. Rama I took this as a sign that the old building had not been sufficient and ordered the construction of a sturdier edifice.

With a stable Siam now emerging, Rama I also dedicated some of his time to promoting the arts, particularly the literary arts. Many of the ‘great classics’ were re-written including one of Siam’s best-known tales, Ramakien, which is derived from the Indian Ramayana. The king supervised the rewriting of Ramakien and is believed to have written parts himself. The story of Ramakien is also told in murals on the walls of the Grand Palace.

It was this dedication to the kingdom that helped Rama I to build a strong Siam. His statecraft set the wheels in motion for future kings of Siam, but it wasn’t without opposition and the threat of Burmese invasion was as real as ever.

Conflicting Forces

In the same year that Bangkok was officially opened, King Bodawpaya of Burma, encouraged by numerous military successes, decided to launch an attack on Siam. The Burmese opened five different fronts at strategic locations including Chiang Mai, Petchaburi, the far southern provinces, the Three Pagoda Pass and the town of Tak. The Siamese responded by deploying three forces and Bodawpaya met with the army led by Siam’s uparat (deputy-king), who was none other than Bunma, the king’s brother. At first, the Burmese appeared to have the upper hand, but after food shortages and an outbreak of smallpox, the Siamese sent Bodawpaya and his troops into retreat, harassing them all the way to Burmese territory.

During these battles, the uparat came into conflict with his brother over a request to execute a number of ministers who had failed to fulfill their duties. Because these ministers were close friends of the king, he denied the uparat’s request but gave him permission to punish them. The guilty ministers were stripped of their ranks and their heads were partly shaved before being marched around the camp.

Rama I and his brother were frequently at odds during his reign and feelings of rivalry existed between them. The king had consistently used his power to undermine his brother’s position and towards the end of his life the uparat planned a coup d’état to overthrow Rama I and place his son on the throne. However, he became ill and died before he could carry out his plan. A number of co-conspirators were discovered and executed.

The Legacy

Rama I was born Thong Duang March 20, 1737 to a high-ranking government officer and his Chinese wife. Though he wasn’t born of royal blood, he rose through the ranks and became king of Siam by virtue of his steadfast character, decisive actions and leadership skills. His rise to the throne also fitted the Buddhist belief of karma and his legitimacy depended not on his bloodline but on ties of incarnation. He claimed to be a Bodhisatta, who had attained good karma through merit making in previous lives, and would become a Buddha in his next life.

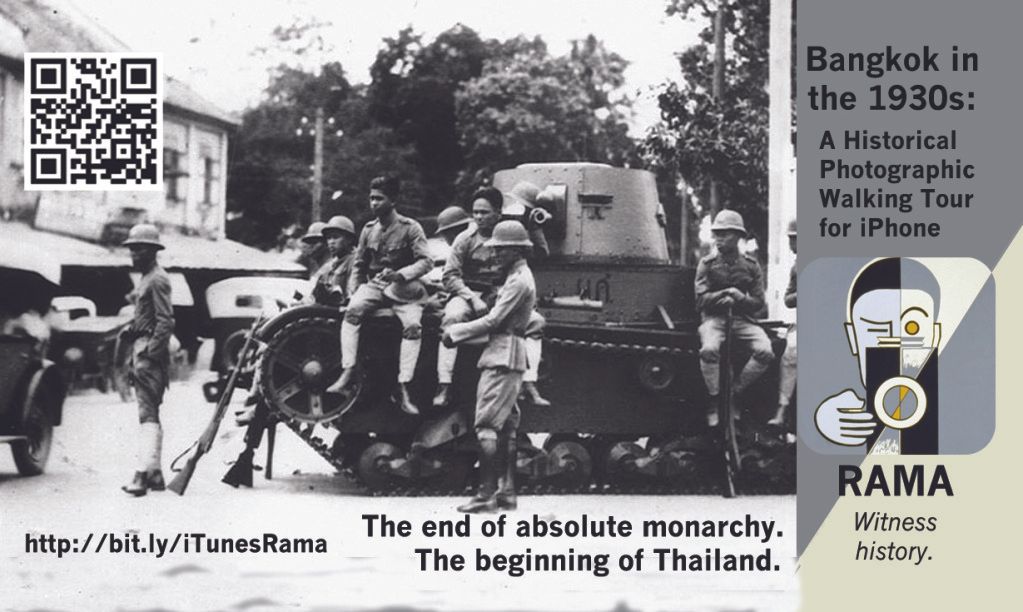

Rama I was a conservative king, quite the opposite of the eccentric Taksin, and he held the pride of the kingdom above all. Through his numerous reforms, Siam started a new chapter in its history which, though veiled in the guise of orthodoxy, was in fact a time of innovation and would eventually lead to westernization and the fall of the absolute monarchy. He died aged 72 on September 7, 1809. He was the father of some 42 children to 28 mothers; divorce lawyers would have loved this guy.

On his death bed Rama I prophesised that his dynasty would last but 150 years. To find out how that prophecy did (at least in part) come true, stay tuned to this blog as we follow the lives of the Nine Kings of the Chakri Dynasty.